Global Mental Health Report

Analysis and writing by

Happier Lives Institute

Commissioned and directed by

Bloom Wellbeing Fund

SHARE

Peter Brietbart

Director

Lily Yu

Director

This report underscores the simple but striking finding that improving global wellbeing requires addressing mental health.

Read the directors’ foreword

When we set out to understand what most shapes a person’s wellbeing, the evidence consistently highlighted mental health. This report underscores the simple but striking finding that improving global wellbeing requires addressing mental health.

The scale of the challenge is vast. Mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, substance use, and schizophrenia are among the most harmful experiences an individual can endure. They are also widespread, affecting more than one in six people globally. And yet, despite their prevalence and severity, mental health conditions remain chronically underfunded. This neglect is particularly acute in low- and middle-income countries, where the majority of the burden falls but where access to effective care is minimal.

What distinguishes mental health from many other global health priorities is not only the severity of the harm, but also the solvability of the problem. Effective, evidence-based, and low-cost interventions already exist. Community-delivered psychotherapy for depression and anxiety, restrictions on lethal pesticides to prevent suicide, and behavioural interventions that reduce cycles of violence all demonstrate what is possible when research, policy, and implementation converge. These approaches go beyond merely mitigating symptoms by restoring functioning, healing relationships, and reinforcing dignity – all outcomes that translate directly into improved wellbeing.

The picture is clear: we know what works. Now the task is to scale it up. The problem isn’t knowledge, it’s investment. Mental health consistently receives only a fraction of the attention and funding its real-world human burden would justify. At a time when philanthropic resources are limited, this imbalance represents both a moral imperative and a practical opportunity. Directing support toward rigorously evaluated, cost-effective interventions can generate impact at a scale that few other areas of global health and development can match.

Bloom was created to respond to this opportunity. By advancing evidence-informed, trust-based, and thesis-driven philanthropy, Bloom supports interventions and research that improve mental health and wellbeing where the need is greatest. But no single fund can address the scale of this challenge alone. Progress depends on a broader community of funders, researchers, and practitioners committed to building the field together.

Bloom isn’t a mental health fund – it’s a wellbeing fund. Yet the evidence is clear that many of the most effective ways to improve wellbeing involve supporting mental health. The evidence presented here demonstrates why mental health must move from the margins to the centre of global health and development. We invite philanthropists and partners who share this conviction to collaborate with us, to fund proven interventions, to invest in the next generation of solutions, and to help ensure that millions more people around the world have the chance not just to survive, but to truly bloom.

Executive Summary

Improving mental health plays a pivotal part in building a happier world

Mental health sits at the heart of human wellbeing. Mental health challenges cause profound suffering and disrupt daily life, yet they remain one of the most neglected global health priorities.

Mental health conditions…

- are common (affecting 1 in 6 people), reducing life satisfaction twice as much as unemployment or divorce.

- are harmful, potentially contributing to up to 85% of suicides, and place a heavy burden on families and communities worldwide.

- are neglected, receiving only 0.2% of international health aid financing despite accounting for 8% of the global burden of ill health.

Our research shows that…

- effective, low-cost and well-evidenced solutions exist, and we highlight community-delivered psychotherapy, suicide prevention through pesticide regulation, and CBT-based youth programmes.

- innovation is growing, but more severe conditions still lack scalable answers, presenting opportunities for research and funding.

And it matters particularly now as…

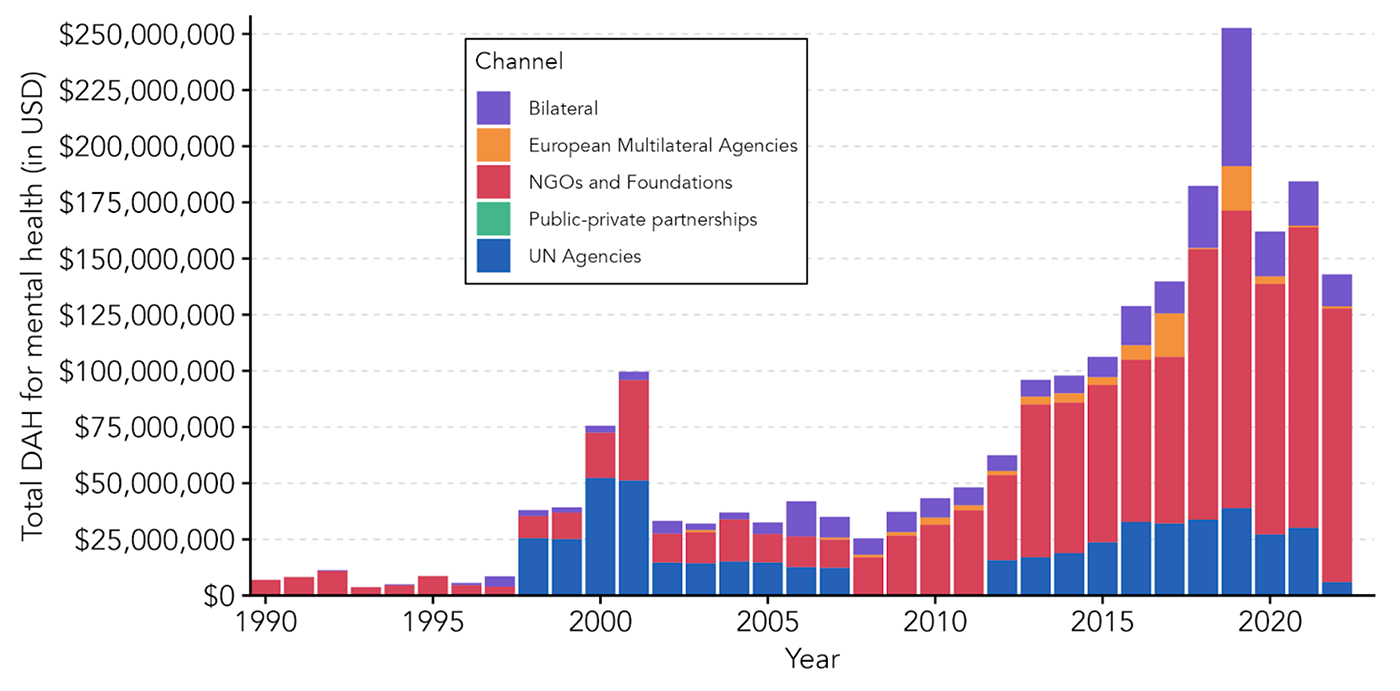

- global mental health funding has fallen sharply from $250 million in 2019 to $150 million in 2022, even as the need rises.

- philanthropists can make an outsized difference by scaling proven interventions, funding new research, and steering the field toward an evidence-driven, wellbeing-focused future.

The case is straightforward, and this report presents the evidence.

The problems

Harmful

Mental health problems (such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, substance abuse, self-harm) can cause intense suffering and interfere with daily functioning. They are among the most misery-inducing of life’s common misfortunes. Depression and anxiety reduce life satisfaction by around 1 point on a 0–10 scale – that’s roughly twice the impact of unemployment, divorce, or chronic physical conditions like arthritis. These problems can also impose hardships on others. About 15% of the suffering experienced by the distressed is shared by those close to them. Mental health problems are potentially attributable to 85% of suicides. These issues can also affect productivity, strain social relationships, and, in some extreme cases, contribute to interpersonal violence.

Common

These conditions are not rare. The most recent and reliable data indicate that 18% of the global population lives with a mental health condition – up from 16% in 2019. Mental health problems represent 7.67% of the health burden worldwide (measured in disability adjusted life years, DALYs), a problem on par with malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/ AIDS combined.

Neglected

Despite making up around 8% of ill health and more than 70% of the global burden of mental ill-health falling on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), addressing these problems receives little funding. In LMICs, governments spend only ~1.31% of their health budget on mental health. Only 0.2% of health-directed international assistance is spent on mental health, and the low investment in mental healthcare shows. Across the world, only 23% of people receive adequate treatment in High Income Countries (HICs). The levels are even lower in LMICs, with only 3% of the population receiving adequate treatment.

The solutions

There are effective, affordable, and easily scalable solutions to many mental health problems — the most cost-effective of which are often delivered where they are needed most, in low-income countries. Some of these approaches are already supported by strong evidence and ready to be expanded; others are promising but require further research and development; and for specific problems, effective solutions have yet to be identified.

Depression and anxiety

For common mental health disorders like depression and anxiety, psychotherapy can be very effective. Moreover, it can be delivered affordably and at scale. Resource constraints have led to innovation and the “task shifting” model, where specialists train lay deliverers, who then provide the therapy. This vastly reduces costs, while research shows that it only leads to a modest (~25%) reduction in effectiveness. This “task-shifting” model has been successfully implemented by charities such as StrongMinds and Friendship Bench, which provide cost-effective and evidence-based care in Sub-Saharan Africa. Amongst available options, this is the most robust and best-researched bet for improving global mental health.

Self-harm and suicide

Restricting access to highly toxic pesticides can be a powerful way to prevent suicide, particularly in rural LMICs where they are a common means. While this approach does not address underlying psychological distress, it can significantly reduce deaths. The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention (CPSP), a philanthropically funded initiative, collaborates with governments to implement such policies and has been positively evaluated by the charity evaluator GiveWell.

Crime and antisocial behaviour

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can be used to prevent crime and improve wellbeing among at-risk youth and former offenders. In Colombia, the charity ACTRA is piloting such an approach, developing interventions grounded in CBT principles to promote wellbeing, social cohesion, and reduce recidivism. Although there is some evidence supporting this intervention, it has not yet been scaled up for implementation by a charity.

Alcohol and substance abuse

Brief interventions and policy reforms (such as regulating alcohol availability) show potential in addressing harmful substance use, though the evidence base is thinner here than for other problems. Philanthropic initiatives, such as Sangath and policy-focused efforts, like Reset Alcohol and Concentric Policies, represent early opportunities for learning about the impact of such projects. Further research is needed to identify the most cost-effective approaches.

Severe mental disorders

For conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, combining medication with psychological and social support is effective in high-income contexts. However, these treatments are costly and difficult to deliver at scale in LMICs. More research and innovation are needed to see if there are clear opportunities for philanthropic funding in these areas. These are the disorders for which there is the greatest uncertainty about what works, but, given the enormous social costs of these conditions, they merit further investigation.

How to help

Most of us know people who have suffered severely from mental health conditions. Many of us ask ourselves what we would give to help restore those people to living a full, flourishing life. Fortunately, we have the means to turn that desire into reality. If we fund the right interventions, philanthropists and governments could effectively and affordably save millions of lives from suffering related to mental health problems.

Despite the scale of the problem, mental health continues to receive far less funding for treatment and research than problems responsible for a comparable disease burden. Alarmingly, international mental health funding has shrunk from $250 million in 2019 to $150 million in 2022 (the year with the latest data), even as the prevalence of mental illness continues to rise.

In this period of scarce and declining funds, philanthropists can have an outsized impact by keeping critical projects alive, shaping field priorities, and steering mental health toward a more effective, evidence-driven future.

How you can help

- Partner with Bloom and the Mental Health Funding Circle to build and strengthen the nascent field of effective giving for mental wellbeing.

- Support high-impact charities delivering proven interventions.

- Advance the evidence base by funding evaluations of promising charities and the research needed to discover the next generation of effective solutions.

- Join the conversation by sharing your ideas, feedback, or questions—we are keen to collaborate. Get in touch if you want to help, but you aren’t quite sure how.

1. Mental health

A big, bad, sorely neglected problem

Mental illnesses are among the most harmful health conditions for overall wellbeing, contributing to over 700,000 suicides worldwide each year. Their effects extend beyond individuals, with about 15% of the distress shared by those close to them. This section explores the profound impact of poor mental health on individuals, families, and communities, and highlights often overlooked solutions.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation defines mental illness as “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour”.

Such problems typically occur due to a combination of risk factors (genetic and environmental) and life stressors. Documents developed by medical organisations, such as the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, catalogue specific mental illnesses and provide a source for consensus-based diagnostic criteria.

In this report, we focus on the most common disorders, which represent about 80% of the global burden of mental illness. These are:

Depression and anxiety

These are the most common mental health conditions, with 5–9% of the world experiencing them at any given time. The lifetime prevalence is much higher.

Substance and alcohol use disorders and conduct disorders

These are experienced by 2-4% of the population at a given time. Alongside other problems such as ADHD and some personality disorders, these are characterised by outward-directed behaviours such as aggression, impulsivity, defiance, or risky acts that can disrupt social functioning and often create visible conflict.

Schizophrenia, psychosis, and bipolar disorder

These are experienced by ~1% of the population at a given time. These are known for disruptions to thinking or perception, such as hallucinations, delusions, disorganised thought, or extreme mood swings.

1.1 Severity: mental ill-health is harmful and life-threatening

Key takeaways from this section:

- Mental illnesses are among the health problems with the worst effects on wellbeing.

- Mental health problems are a major cause of most of the yearly 700,000+ global deaths due to suicide,

- Around 15% of the suffering experienced by the distressed is shared by those close to them.

1.1.1 Harm to individual wellbeing

“The depressed person was in terrible and unceasing emotional pain, and the impossibility of sharing or articulating this pain was itself a component of the pain and a contributing factor in its essential horror.”

David Foster Wallace in “The Depressed Person”

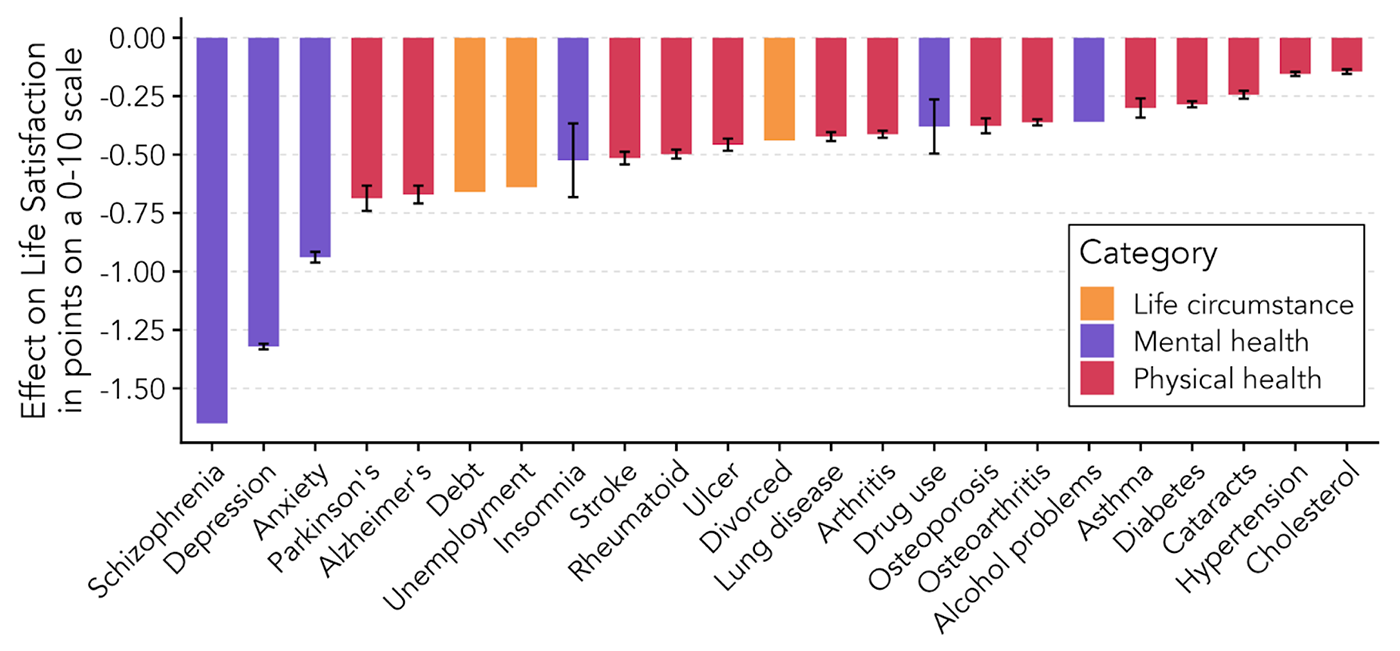

Depression, alongside other mental health problems, is one of the conditions most harmful to wellbeing. Below, we present the associations between several mental health problems and life satisfaction based on estimates collected from the literature; these represent reductions on a 0-10 scale. The figure illustrates that depression and anxiety are much more strongly associated with lower wellbeing than many health conditions, like arthritis, or economic misfortunes such as unemployment.

Figure 1: Impact of mental health problems on life-satisfaction of European adults

Note: The primary source for this figure is the Happiness Research Institute (2020).

1.1.2 The loss of life

“Many mental health diagnoses are associated with a drop in life expectancy as great as that associated with smoking 20 or more cigarettes a day. There are likely to be many reasons for this. High-risk behaviours are common in psychiatric patients, especially drug and alcohol abuse, and they are more likely to die by suicide.”

Dr Seena Fazel of the Department of Psychiatry at Oxford University

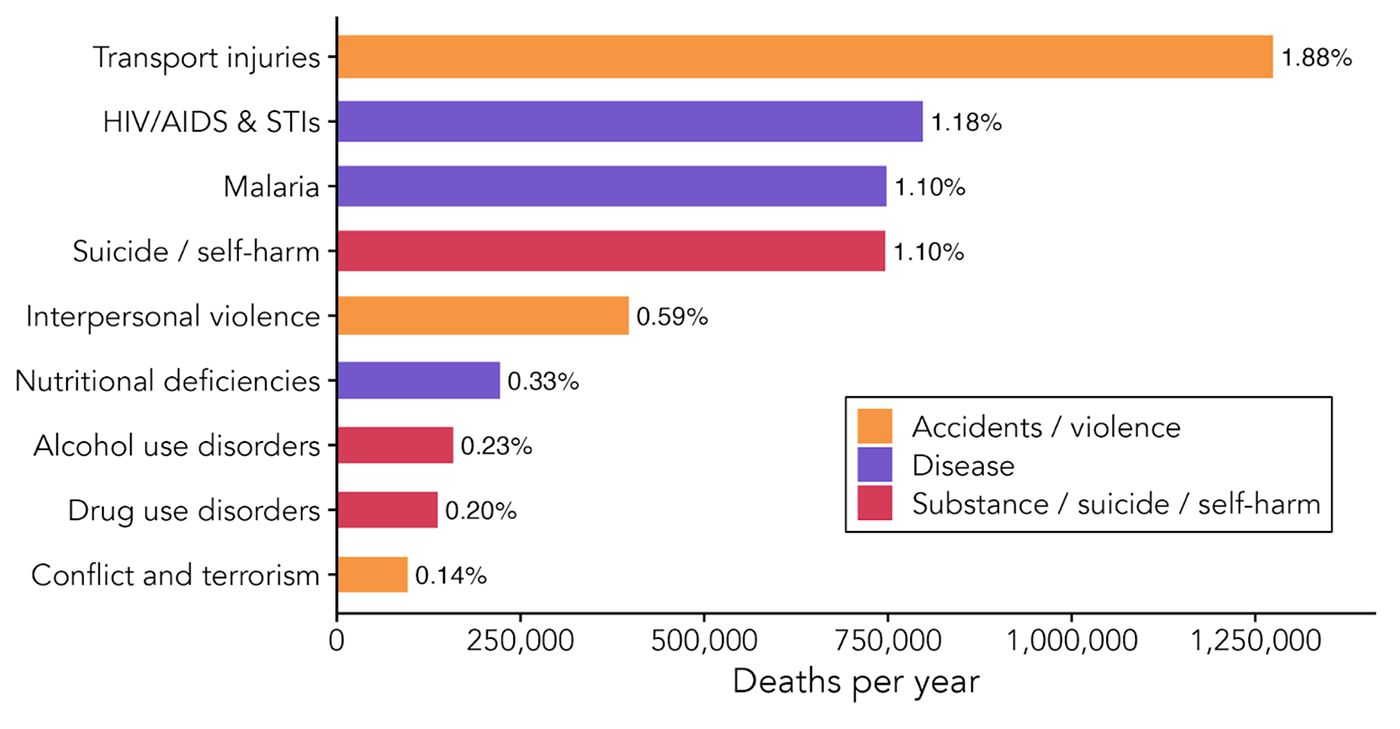

Mental health problems cut thousands of lives short, with the clearest cause being suicide, of which mental health disorders are the most frequent cause.

Globally, suicide accounts for nearly 700,000+ deaths per year. The number of deaths is similar to the number killed by malaria or HIV/AIDs, and 11 times more than those killed by war. Alcohol and substance use disorders also lead to hundreds of thousands of deaths globally, another 0.4% of all deaths. These include not only the deaths of individuals experiencing the condition, but also of others (due, e.g., to accidents, acts of violence, and so on that may take place during acute intoxication). For example, alcohol use contributes to a much larger share of deaths than is attributable to alcohol use disorder alone (5% compared to 0.4% of all deaths globally).

Figure 2: Global yearly deaths according to condition from the IHME.

Note. The percentage at the end of each bar represents the global percentage of deaths attributable to each cause.

People with mental health problems (especially severe ones) are also more likely to be the subject of, and to commit, violence. As a striking illustration, closing down mental health institutions in Brazil caused a spike in homicides of 7%.

1.1.3 Harms to others: spillovers

“Can I see another’s woe, / And not be in sorrow too? / Can I see another’s grief, / And not seek for kind relief? / Can I see a falling tear, / And not feel my sorrow’s share? / Can a father see his child / Weep, nor be with sorrow filled?

William Blake, On Another’s Sorrow (1789)

The impact of mental health problems is not contained in the individual experiencing them; they often affect a broader group. We use the term ‘spillovers’ to refer to the wellbeing effects that occur in people beyond the individual experiencing the mental illness. Because the burden of these problems is felt by whole families and communities, solving them yields outsized benefits. We note a few examples:

- For every suicide, there is broad and long-lasting grief at what is often an inexplicable and sudden loss.

- About 15% of the suffering experienced by the distressed is shared by those close to them. Mothers falling into depression casts a nearly decade-long shadow on the mental health of their children. Conversely, treating depression in Pakistan led mothers to spend more time playing with their children, who were also more likely to be fully immunised and less likely to suffer from diarrhoea.

- While people with mental health problems are around 3 times more likely to be charged with a crime, increasing access to mental health care reduces crime in the USA, so much so that it pays for itself.

- The WHO reports that 12 billion days of productivity are lost to poor mental health annually, with some estimating this reduces GDP by 5%. This work is lost because the presence of mental health problems hinders education and skill acquisition, lowers productivity, lowers employment, and adds health expenditures. But treating mental health increases the time spent working, suggesting it could boost productivity.

1.2 Size: A common, global and growing problem

Key takeaways from this section:

- Mental health conditions are one of the most common sources of illness, affecting 1 in 6 individuals.

- They also represent 7.67% of the world’s health burden, comparable to malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS combined.

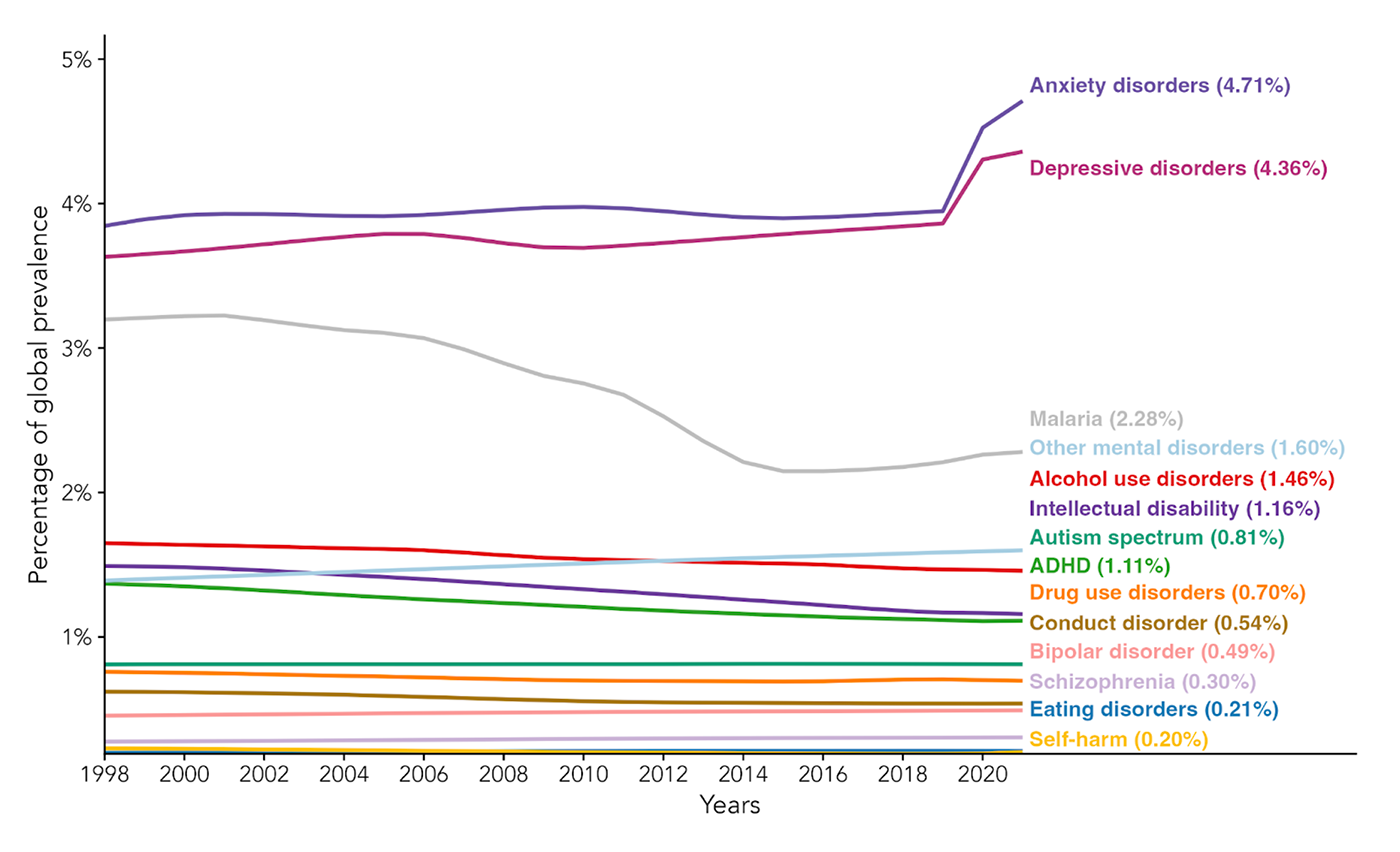

Mental health disorders affect ~1.4 billion people or 17.65% of the global population.

Unfortunately, the share of people with mental health disorders has been growing recently, especially for depression and anxiety. This is up from 16.34% in 2019, and with population growth, far more people are suffering—the total number will continue to rise without a massive expansion of effective treatments.

Figure 3: Prevalence (how many people have a particular problem at that specific point in time) of health problems in the world across time.

The prevalence of mental health problems has not improved over time. Although economic development has increased over the period displayed in Figure 3, the prevalence of most mental disorders has remained stable or increased. In contrast, economic development reduces many other problems such as poverty and physical ill health (e.g., see malaria in Figure 3). Further, richer countries do not necessarily have better mental health – this is puzzling, also known as the ‘treatment-prevalence paradox’.

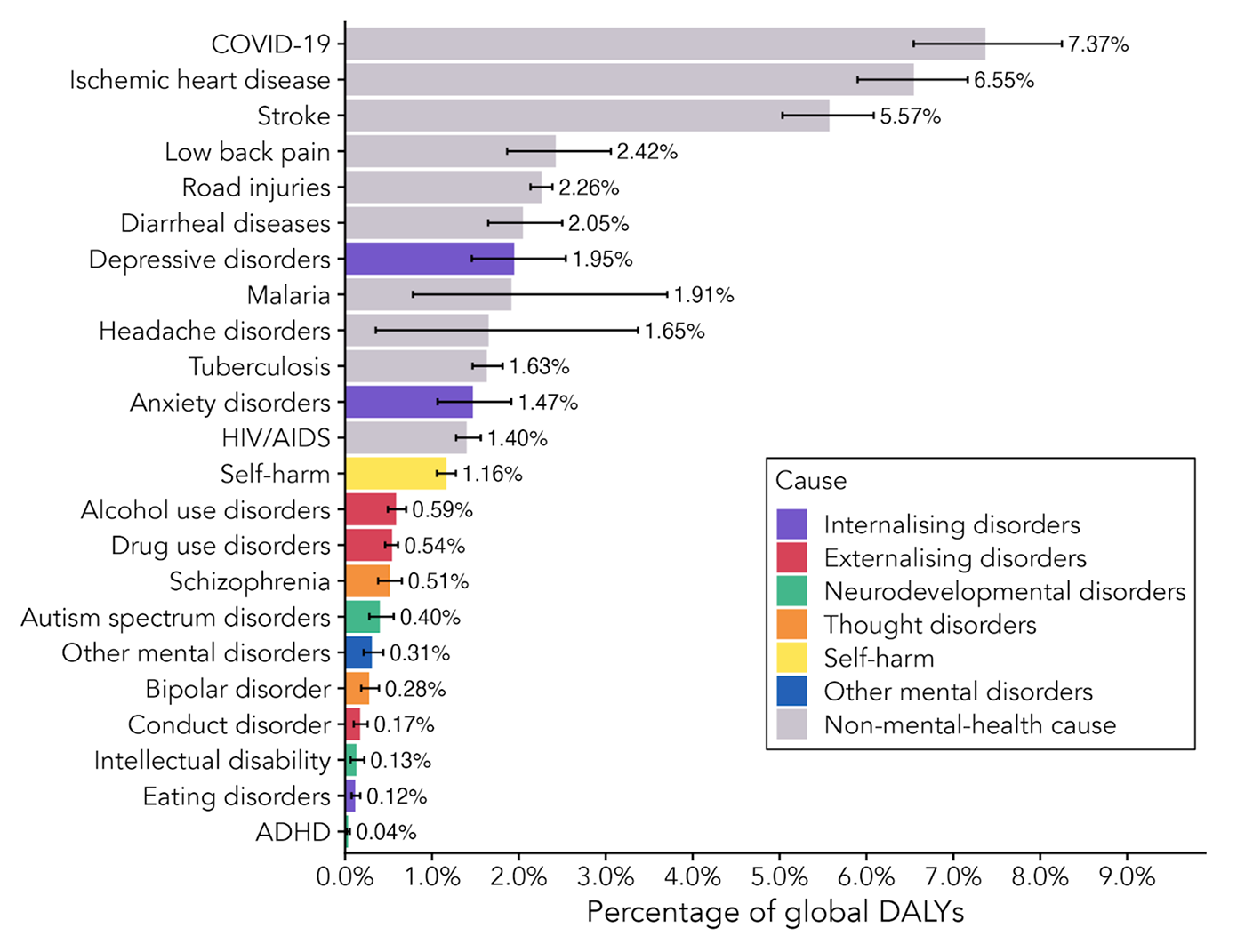

Mental health problems account for a significant portion of the global health burden. Combined, they represent 7.67% of the world’s ill health. The health burden is calculated using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). A DALY represents one year of healthy life lost due to illness, disability, or premature death. Some experts argue this method leads to a substantial underestimate on the grounds that DALYs fail to capture the real suffering of mental health.

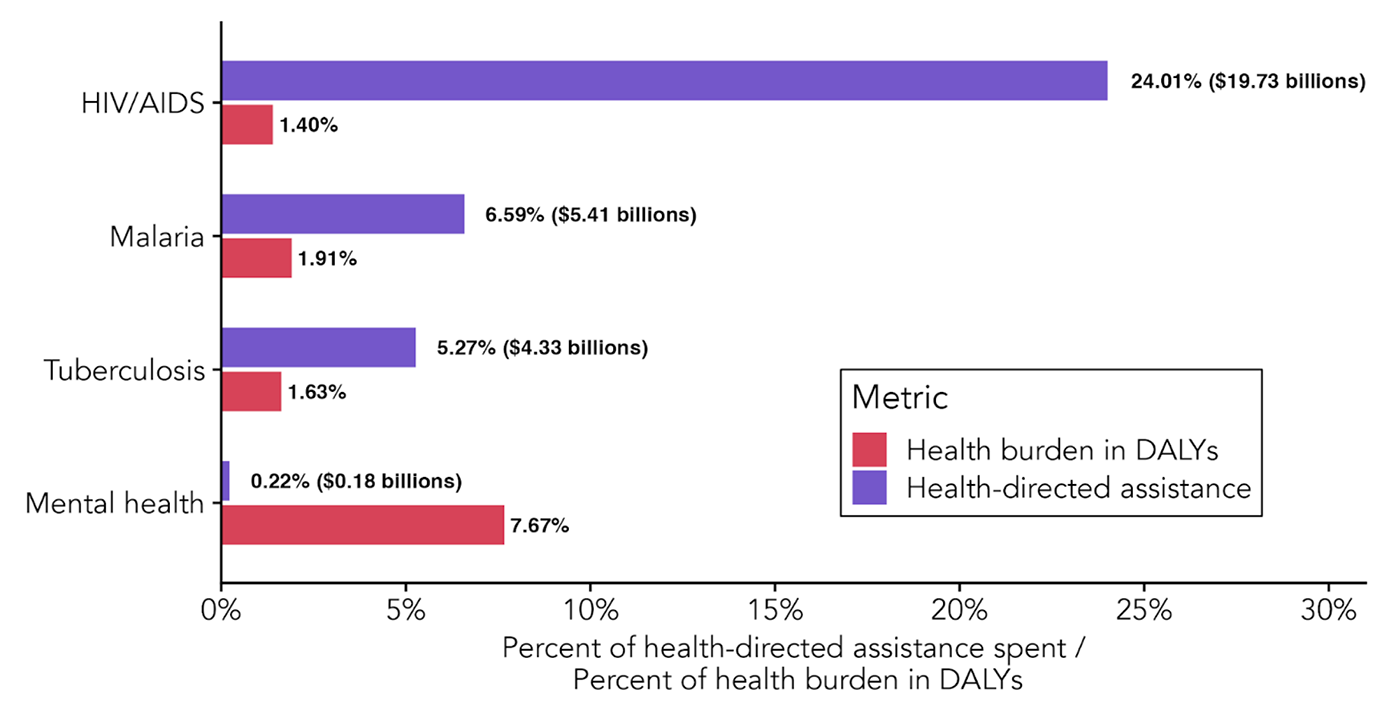

This data means that mental health problems account for a greater health burden than malaria, tuberculosis and HIV combined.

Figure 4: Share of the world’s burden of disease across causes in the latest year with data (2021).

1.3 Neglected solutions

Key takeaways from this section:

- Despite constituting 7.67% of the global health burden, mental health conditions receive, according to the most recent available figures:

- 2.3% of government health spending globally; this is 3.8% in HICs and 1.31% in LMICs.

- 0.22% of health-related aid funding, which overwhelmingly goes to LMICs.

- The aid share is much less than the 35.87% of all health aid for malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDs combined, despite representing a similar health burden.

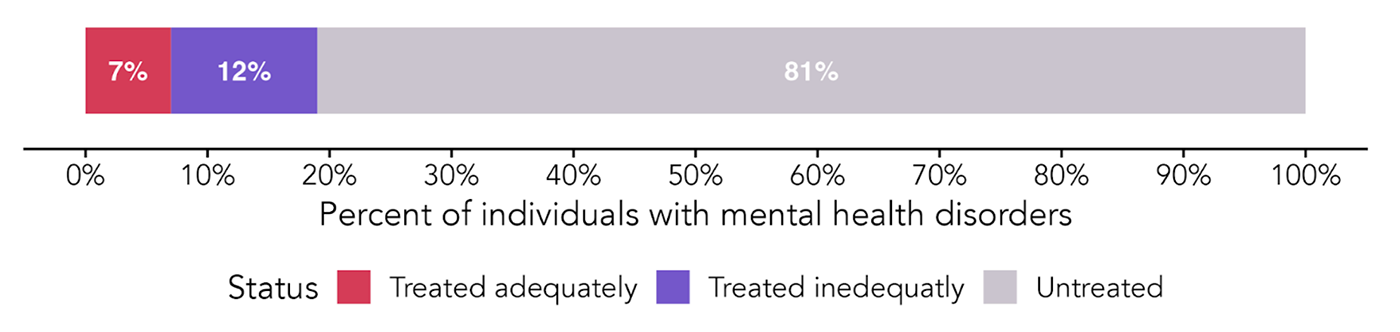

- Only 7% receive adequate treatment globally, but even less in low-income countries (e.g., 3% for depression in LMICs).

- The treatments that are delivered in LMICs are often ineffectively spent, with 80% going to psychiatric hospitals where the cure is sometimes worse than the disease.

Mental health problems make up 7.67% of all ill-health globally. However, the typical government spends 2.3% of its health budget on mental health problems. It’s only slightly more in HICs, with 3.8% of health budgets allocated to mental health. The situation is worse for LMICs, where governments spend ~1.31% of their health budgets on mental health.

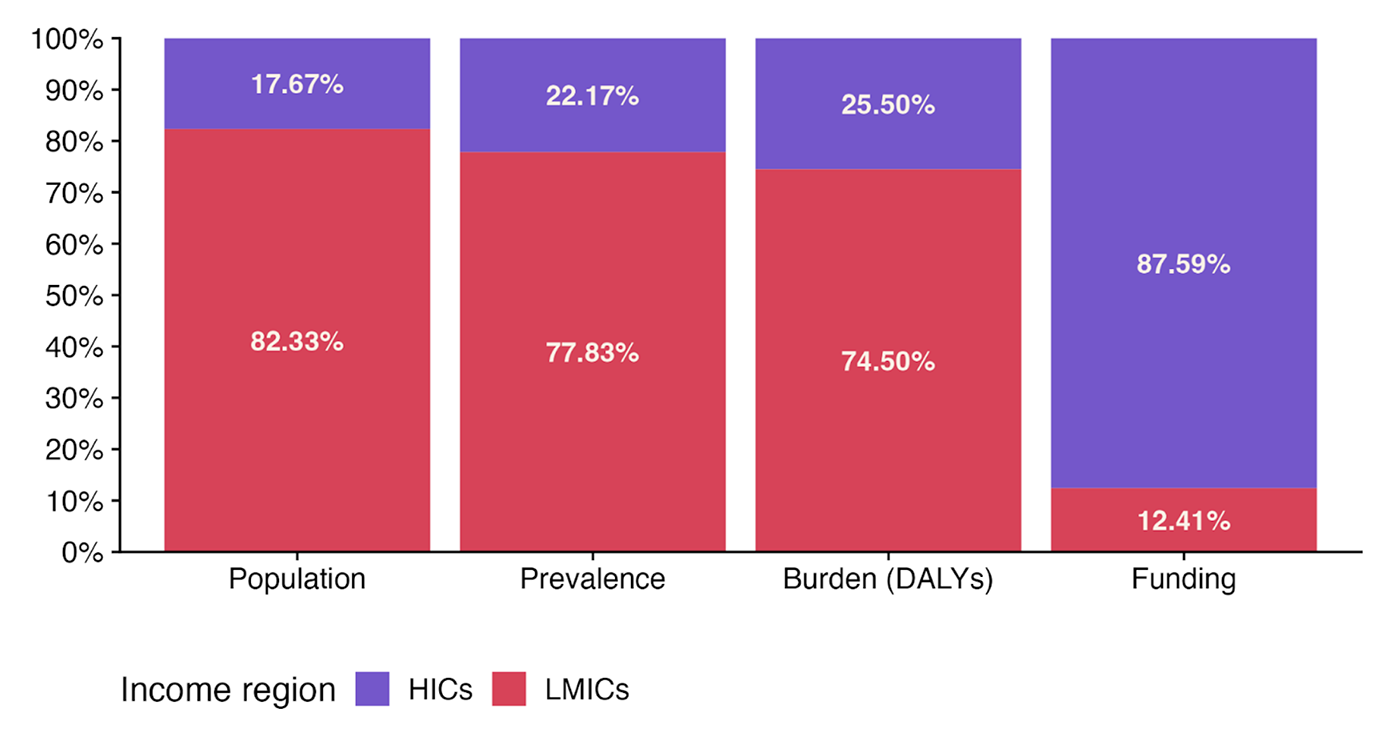

We illustrate the mismatch between where the problems and the money are in the figure below. It shows that most people with mental health problems live in LMICs (80%), while 88% of the spending to solve these problems occurs in HICs.

Figure 5: Unequal distribution of burden and funding across the world.

The situation is even starker for aid and philanthropy. There, mental health problems receive only 0.22% all international health assistance (much less than the 35.87% for malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDs combined, despite representing a similar health burden).

Figure 6: Health-directed development assistance for problems primarily in LMICs.

Compared to other worthy causes, mental health typically receives less funding for the same health burden. Addressing mental health problems is therefore neglected compared to many other aspects of global health. The same is true for funding research, which we return to in Section 3. This neglect isn’t merely a concern in the abstract. It means that fewer people receive treatment. However, it also means that there’s a considerable amount of low-hanging philanthropic fruit when it comes to plugging the massive gap in funding and treatment.

1.3.1 Low treatment is the consequence of low funding

The low investment in mental healthcare shows. Globally, ~19% of people with mental health problems receive treatment, but only 6.9% receive ‘adequate treatment’ – see the footnote for a definition. The levels tend to be lower when looking at LMICs – a mere 3% receive adequate treatment for depression in LMICs. While funding isn’t the only factor – social factors like stigma also play a role – lack of funding is a critical barrier keeping more people from accessing treatment.

The aid, government spending, and treatment gap figures are from before the 2025 aid cuts, so the current situation is likely worse.

Figure 7: Percentage of people treated for mental health globally.

1.3.2 Money poorly spent?

Despite current investments being exceptionally small, these are also often ineffectively spent.

Of spending on mental health in LMICs, 84% goes to mental hospitals, compared to only 32% in HICs.

The focus on hospitals could be a problem because psychiatric hospitals are often located in the wrong place to help the majority of the population, and they are often less helpful than they could be. Molodynski et al.’s (2017) academic description is one example of concerns about their effectiveness:

“The minority of people who do receive state mental healthcare will generally do so at Butabika Hospital and be subject to overcrowding, poor conditions and coercion […] While the individual may finally receive some form of treatment, the trauma involved may have additional long-term consequences.”

While psychiatric hospitals have their role, more cost-effective care can often be provided in primary care and community settings by non-specialist providers. High-income countries have already made this shift away from inpatient treatment—a model we discuss in detail in the next section.

2. Solvability

We can close the treatment gap with existing tools

The global burden of mental illness is immense, yet there are proven, scalable, and practical solutions available. In this section, we outline the current understanding of various mental health disorders and explore effective strategies for making meaningful progress.

Introduction

“I’ve been tied many times and given bitter medicines through the nose[…]. They give you roots, leaves as medicine. Their treatment was always unsuccessful. My mother and father would come and take shifts. One time I escaped with the rope tied to a log. They caught me and I pleaded with my mother to bring me home, I really suffered in that place.”

Carlos, a man with an unspecified mental health condition who was held against his will in a faith healing centre in Mozambique

We can do so much better.

Across the world, thousands of people are chained in squalid conditions and forced to undergo ineffectual and potentially harmful treatments for improperly diagnosed mental health conditions. Sometimes this is in psychiatric hospitals, but often it’s in households, sheds, and non-medical establishments. For example, a Human Rights Watch report documented many such cases. Their accounts are harrowing.

There are many potential approaches to improving mental health. Still, given limited resources, the key question to answer if you want to improve lives the most is: which interventions are the most cost-effective? In this report, we focus on the best-bet solutions to each condition—interventions that not only offer strong returns in wellbeing per dollar, but also meet the following criteria:

✓ Well-evidenced, particularly in low-income settings.

✓ Scalable, with evidence that the intervention maintains its effectiveness at a larger scale.

✓ Actionable, with a real-world organisation currently delivering the intervention.

For many mental health conditions – such as depression, anxiety, anti-social behaviour, and self-harm – there are already solutions that meet all these benchmarks. Where those do not yet exist, we identify the key gaps in evidence or implementation capacity, and highlight priority areas for future research or investment.

How to estimate cost-effectiveness

Where possible, this report evaluates interventions using wellbeing-adjusted life years (WELLBYs)—a standardised measure also adopted by UK and New Zealand Treasury guidelines for assessing non-monetary policy impacts. Most evaluations come from the Happier Lives Institute and typically work like this:

To estimate an intervention’s impact, literature reviews are conducted, effect sizes from high-quality studies are extracted, and individual studies are combined in a meta-analysis to model the initial effect and how the effect changes over time. Spillover effects on others (e.g., household members) are also included.

Adjustments are applied to the estimated impact to better reflect real-world effectiveness. These adjustments account for risks to internal validity (e.g., publication bias or low-quality evidence) and external validity (e.g., differences in population, dosage, or delivery scale).

Finally, the overall benefit is divided by the cost of the intervention, typically based on real-world data from the implementing charity, to determine how many WELLBYs are generated per $1,000 donated. These evaluations allow one to compare which interventions deliver the most wellbeing per dollar.

Table of current landscape of solutions (best viewed on computer)

We summarise the current landscape of solutions below. Each problem area is explored in detail throughout the rest of this section in order from most to least easily solvable.

| Problem | Best current solution | Does it work? | Cost-effective? | Fundable orgs | Scalable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalising disorders (anxiety & depression) | Scaling lay therapy | Yes, therapy cures half of cases (in at least 100 RCTs) in the short term, and 5% remain cured for ~5 years longer (in one RCT). | Yes. 40–50 WELLBYs per $1k (4–6× better than cash transfers). | In-person: 4+ (StrongMinds, Friendship Bench); Digital: 3+ (Overcome, Kaya Guides) | Yes. Case: Improving Access to Psychological Therapies in the UK. |

| Externalising disorders (conduct → crime) | Scaling lay therapy | Yes, therapy reduces criminal and anti-social behaviour (10+ RCTs), potentially reducing 34 crimes per year even after 10 years (1 RCT). | Yes. 20–80 WELLBYs per $1k (2–8× better than cash). | In-person: 1+ orgs (Actra) | Untested. It may be more complicated than standard therapy. |

| Self-harm and suicide | Banning highly toxic pesticides | Yes. Reduces suicides by 5–45% (based on 4 non-causal studies). | According to GiveWell, close to the top life-saving charities. | Advocacy: 1+ orgs (CPSP) | Yes. Case: Pesticide bans in South Asia. |

| Externalising disorders (substance use) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear. Needs evaluation. | Unclear. Needs evaluation. | Unclear. |

| Thought disorders (schizophrenia) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear. Needs evaluation. | Unclear. Needs evaluation. | Unclear. Needs evaluation. |

2.1 Common mental health disorders like anxiety and depression

“Psychotherapy is the best initial treatment choice for depression […] Indeed, if only psychotherapy was a pill, it would have been a blockbuster drug. But psychotherapy isn’t a pill and most people who would benefit from psychosocial interventions globally cannot access them.”

Vikram Patel, a Harvard-based mental health researcher writing in the Lancet in 2022

The problem

Anxiety and depression are the most common and disabling internalising disorders, as well as the most burdensome mental health conditions in general (~50% of the mental health burden, and are experienced by ~6% of the world). Thankfully, there are cheap and effective solutions that meaningfully reduce their symptoms. Currently, psychotherapy delivered by lay practitioners is the best evidenced, most cost-effective, and scalable intervention for treating anxiety and depression.

Best rollout-ready solution: psychotherapy delivered by lay practitioners

Psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy, is a relatively broad class of interventions delivered by a trained individual who aims to improve their patients’ mental health through structured discussions, as well as activities and skill training, such as practising gratitude or improving social interactions.

Is it effective?

Comprehensive reviews confirm that psychotherapy of almost any kind effectively treats depression, anxiety, and other conditions in both high- and low-income countries.

Despite this evidence, studies find that people often underestimate therapy’s effectiveness, which can discourage individuals from seeking treatment and funders from investing in mental health programs.

In reality, therapy reduces depression symptoms by at least half in 42% of cases. And these benefits can last. In one trial of CBT in Pakistan, researchers found that depression rates were 17% lower seven years later.

Psychotherapy also improves economic outcomes by allowing people to work more, alleviating the poverty that’s also a cause of poor mental health.

Notes from a field visit to Friendship Bench (Zimbabwe)

“Before encountering Friendship Bench, Betty was in a state of deep distress, feeling suicidal and overwhelmed by her circumstances. When she started attending sessions with the grandmothers, she found a compassionate ear and practical support. Over time, her mental health significantly improved. Betty spoke about how the sessions provided her with tools to manage her emotions and a community where she felt understood and supported. Joining a support group became a critical part of her recovery process. Through this group, she learned to crochet, an activity that not only brought her joy but also provided a source of income. Betty also improved her relationship with her four children, fostering open communication and support.”

Michael Plant (2024), Director of the Happier Lives Institute, giving an account of a previous client of Friendship Bench, which scales psychotherapy delivered by peers.

Is it cost-effective?

Yes, the charity evaluator, the Happier Lives Institute, estimates that funding this sort of psychotherapy returns 40 to 49 WELLBYs created per $1,000 invested.

Psychotherapy is thus 5-6 times as cost-effective as unconditional cash transfers to people in LMICs. It is also among the most cost-effective and best-evidenced ways to improve wellbeing globally, based on present evaluations.

This cost-effectiveness is driven by its low delivery cost. It’s less than $50 to provide a basic course (six weekly sessions) of psychotherapy for someone experiencing depression. This low cost is possible for several reasons. First, short courses of therapy are about as effective as longer ones.

Second, non-experts can be trained in a matter of months to deliver psychotherapy effectively (‘lay-delivery’, ‘task-shifting’, or ‘task sharing’).

Third, lay practitioners are often willing to provide therapy on a volunteer basis. Together, these mean the effective treatment can be delivered at a low cost – without the need to rely on a scarce and expensive pool of experts.

Does it scale?

Many interventions don’t survive scaling. But psychotherapy can scale and maintain its efficacy. StrongMinds and Friendship Bench are examples that demonstrate how therapy can be delivered to hundreds of thousands in low-resource settings.

There’s also evidence that treatment at this scale can maintain its efficacy. A causal study of the UK’s expansion of access to therapy, a programme called Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), found that, even as it was being delivered to millions, it remained as impactful as small-scale studies suggest.

Is it fundable?

Yes. There are numerous organisations across the world already focusing on scaling the delivery of psychotherapy for anxiety or depression through in-person or digital modes of delivery.

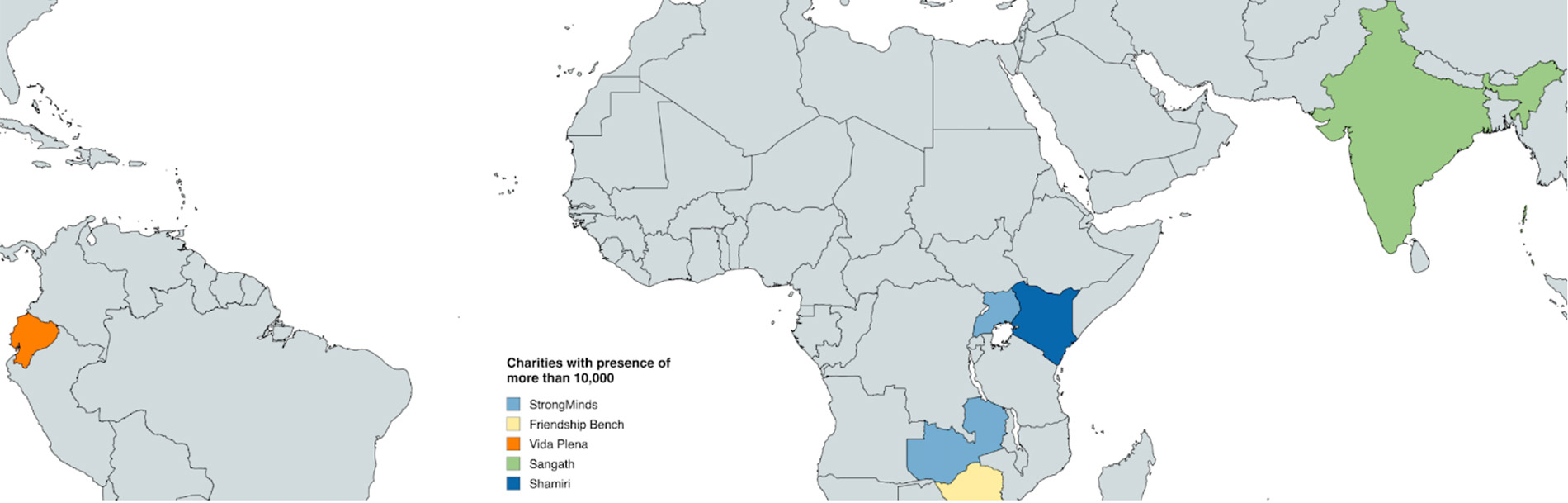

StrongMinds, Friendship Bench, Shamiri, FineMind and Vida Plena deliver in-person programmes. Overcome, Kaya Guides and Canopie deliver remote therapy and digital interventions. We discuss these organisations in more depth in Section 3.

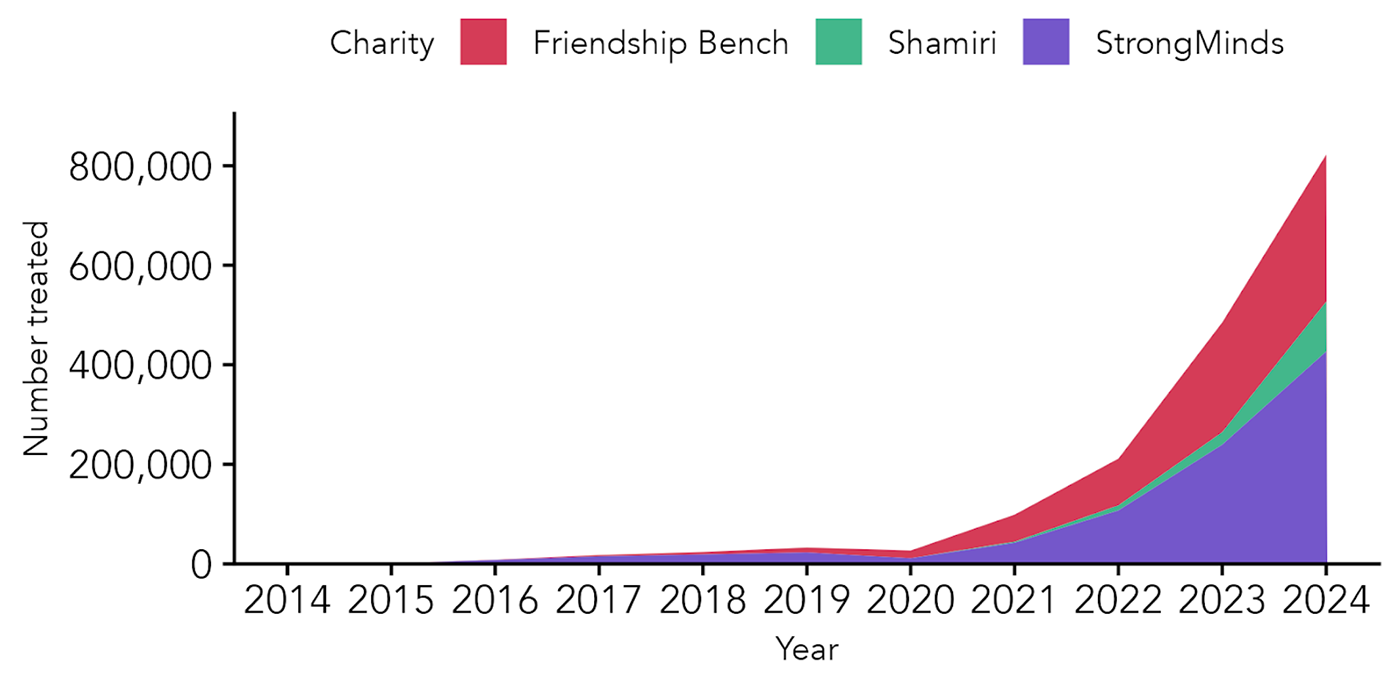

The scale-up of treatment by the most prominent organisations we mentioned above has been massive, with treatment expanding around 10-fold from 2020 to 2024.

Figure 8: The change in the number treated by selected psychotherapy charities in LMICs

Note: We excluded FineMind and Vida Plena from the graph since they are still at a relatively small scale and their contribution is not visible

Other solutions

Depression and anxiety are also commonly treated with drugs or a combination of drugs and therapy.

Individually, therapy and drug treatment appear to both be comparably effective in the short-term, although therapy’s effects seem to last longer, meaning the total benefit is greater for therapy.

Combined treatment is more effective than either drug treatment or therapy alone.

But psychotherapy appears to be better suited for more resource-constrained settings. Drugs to treat anxiety and depression are expensive, need to be stored properly, can have serious side effects, and require a professional (often a psychiatrist) to prescribe. Psychotherapy, by contrast, can be delivered by non-experts with comparable effectiveness (it’s ~25% less effective), but at a fraction of the cost.

There are also many ways to improve anxiety and depression symptoms beyond drugs or psychotherapy, such as cash transfers, mindfulness programmes, exercise, and for children, better nutrition and early education. Unfortunately, most of these are less well studied, established, or do not create large enough changes to justify inclusion as a clinical treatment.

2.2 Self-harm and suicide

“As you huddle around the torn silence,

Each by this lonely deed exiled To a solitary confinement of soul,

May some small glow from what has been lost

Return like the kindness of candlelight.”

The first stanza of John O’Donohue’s For the Family and Friends of a Suicide

The problem

Suicide is the second-highest cause of death unrelated to disease, accounting for nearly 700,000+ deaths per year.

Best rollout-ready solution: reducing access to highly toxic pesticides

Pesticides might have been the method by which between 14-20% (110,000-168,000) of suicides occurred between 2010 and 2014, and millions since the green revolution. Most of these suicides occur in LMICs.

By reducing access to lethal means such as dangerous pesticides (i.e., means restriction), suicide rates can be reduced. This works because suicide attempts are often the result of transient episodes of despair, so removing certain pesticides, which are easily available and people know can be lethal, removes a means of spontaneous suicide attempts.

Once they subside, people rarely re-attempt. One may think that if someone is intent on suicide, they’ll do it regardless of the means. This is not true. Experts estimate that the overwhelming degree of people who attempted suicide do not re-attempt, ranging from 4% to 20% in 5 years.

Is it effective?

Evidence suggests that bans of the most toxic pesticides (WHO Class I toxicity) can dramatically reduce suicide rates due to pesticide poisoning (range 28-92%, 9 studies) and general suicide rates (7% to 45.1%, 4 studies). However, it must be emphasised that removing a means of suicide, or reducing suicide attempts, does not in itself take any emotional suffering away, which is what other interventions like psychotherapy can do.

Is it cost-effective?

Charity evaluator GiveWell recommends restricting pesticides as a highly cost-effective opportunity for saving lives, and the WHO estimates that this is among the most cost-effective interventions for improving health outcomes within the mental health domain. We note that making comparisons between the quality and quantity of life is not straightforward.

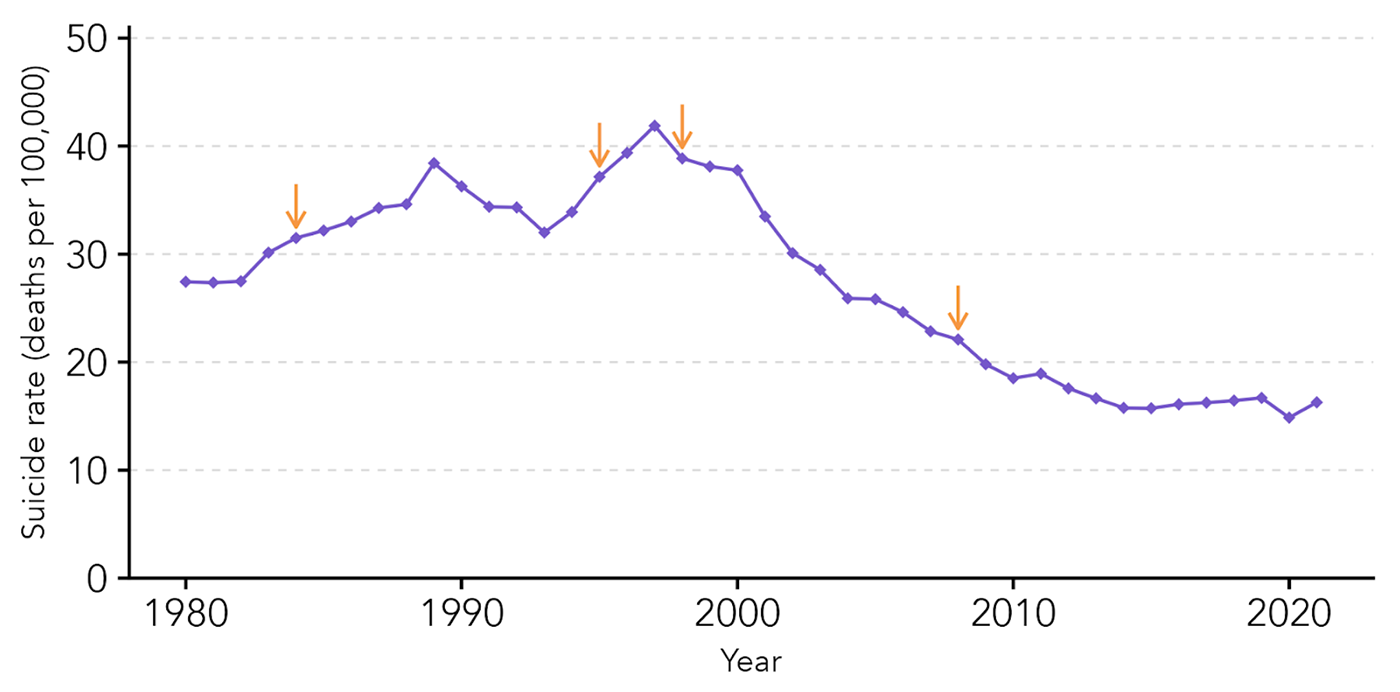

Does it scale?

Yes. The case of Sri Lanka is illustrative. Suicides gradually increased after the widespread use of pesticides started in the 1960s. After a series of pesticide bans, they stabilised and decreased dramatically.

Figure 9: Suicide rates over time in Sri Lanka. The arrows represent different pesticide bans.

Is it fundable?

Yes. The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention (CPSP) is a philanthropically funded research and policy initiative within the University of Edinburgh. They claim to be the only global initiative working on this problem. GiveWell said “We are confident (95%) that dichlorvos and the three-gram tablet form of aluminum phosphide [highly toxic pesticides] would not have been deregistered without CPSP’s involvement.”, estimating it saved 366 lives per year in Nepal.

Other solutions

As mentioned above, restricting means does not, in itself, address the underlying problems that lead to suicidality. Suicidality can also be addressed by treating the underlying mental health conditions, given that the percentage of suicides attributable to mental health disorders is estimated to be between 60% and 98%.

Therapies directly targeting suicidality have been shown to reduce suicide attempts by 28% and self-harm repetition by 65%. Other interventions, such as crisis lines, were beyond our scope here, but we hope future research will investigate them.

2.3 Conduct problems, antisocial behaviour, and criminal behaviour

“If, 10 years ago, you told me that eight weeks of therapy plus a little cash could turn a significant proportion of them away from that life, I’d have scoffed. But it’s true.”

Chris Blattman, University of Chicago economist and author of Why We Fight

The problem

Conduct disorders are “characterised by repetitive and persistent patterns of antisocial, aggressive or defiant behaviour”. These are behaviours which, if particularly costly to others, are criminalised. Notably, conduct disorders are a key predictor of criminal behaviour, with around 2/3rds of people involved in the US criminal justice system having conduct or related disorder (compared to general rates of around ~10%). Involvement with criminal justice systems is also related to high rates of other mental disorders, such as depression.

Best rollout-ready solution: Lay-delivered CBT

Psychotherapy, notably cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), is not just effective for treating common mental health disorders like anxiety and depression; it can also reduce aggressive and criminal behaviour (see Section 2.3).

Is it effective?

CBT is effective at reducing aggressive behaviour in general.

The general approach of trying to change antisocial behaviour through psychological interventions seems to work in a variety of contexts. This applies more specifically to reducing criminality. CBT has been shown to prevent anti-social behaviour through decreasing impulsivity, anger issues, and identification as an outcast/criminal.

Even 10 years after it was delivered, the programme found large reductions in criminality (34 fewer reported thefts a year, about a 50% reduction) and improvements in the mental wellbeing of its recipients. Notably, these effects showed practically no signs of decay between the first and tenth year follow-ups.

Is it cost-effective?

Yes. After accounting for programme expenses, the authors of the original study concluded their results imply a cost of roughly $1.50 per crime avoided. The charity evaluator, the Happier Lives Institute (who co-authored this report), estimates that, if scaled, CBT to reduce crime could return 21 to 80 WELLBYs created per $1,000 invested. This is 3-10 times as cost-effective as unconditional cash transfers to people in LMICs.

Similar to psychotherapy for depression, costs are brought down in large part by training non-experts to deliver psychotherapy (‘task-shifting’ or ‘task sharing’) instead of relying on too few and too expensive expertly trained professionals (see Section 2.1 for more details).

Does it scale?

Maybe. There are no cases of it scaling widely yet. It follows a proven formula that has been scaled with other types of therapies: using peer facilitators instead of expensive experts. But it involves a harder-to-reach population. The success of the intervention may depend heavily on the context, potentially posing difficulties for scaling.

Is it fundable?

Yes. Acción Transformadora (ACTRA) is currently developing a programme based on the best evidence to be delivered in Colombia. A preliminary assessment of a similar programme by HLI suggests it could be very cost-effective (McGuire et al., 2025a).

Other solutions

Anti-social behaviour can be decreased through a range of other psychological interventions, such as parenting or school-based programmes.

Parenting programmes

Parenting programmes that attempt to improve development also reduce behavioural problems. Previous research has found that these can be cost-effective. However, they are more effective at reducing behaviour problems when they are specifically designed to do so.

School-based programmes.

A programme in India, where the school environment was encouraged to be healthier and kinder, resulted in a decrease in bullying and an improvement in mental wellbeing. Sangath, a mental health and research charity in India, is scaling this intervention (this is one of their programmes among many).

2.4 Alcohol and substance use

“My pop was real big. He did like he pleased. That’s why everybody worked on him. The last time I seen my father, he was blind and diseased from drinking. And every time he put the bottle to his mouth, he didn’t suck out of it, it sucked out of him until he shrunk so wrinkled and yellow even the dogs didn’t know him.”

Chief Bromden from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

The problem

Alcohol and substance use disorders are tightly related disorders; both are defined by a dependency on a substance that impairs daily functioning. They are the 4th and 8th most common mental health disorders, affecting 1.46% and 0.70% of the population.

While moderate or in-the-moment drinking is associated with happiness, there’s considerable evidence relating drinking problems to decreased mental wellbeing of the individual. Substance use disorders, like alcohol, are associated with adverse effects on the mental health of the user and their family members.

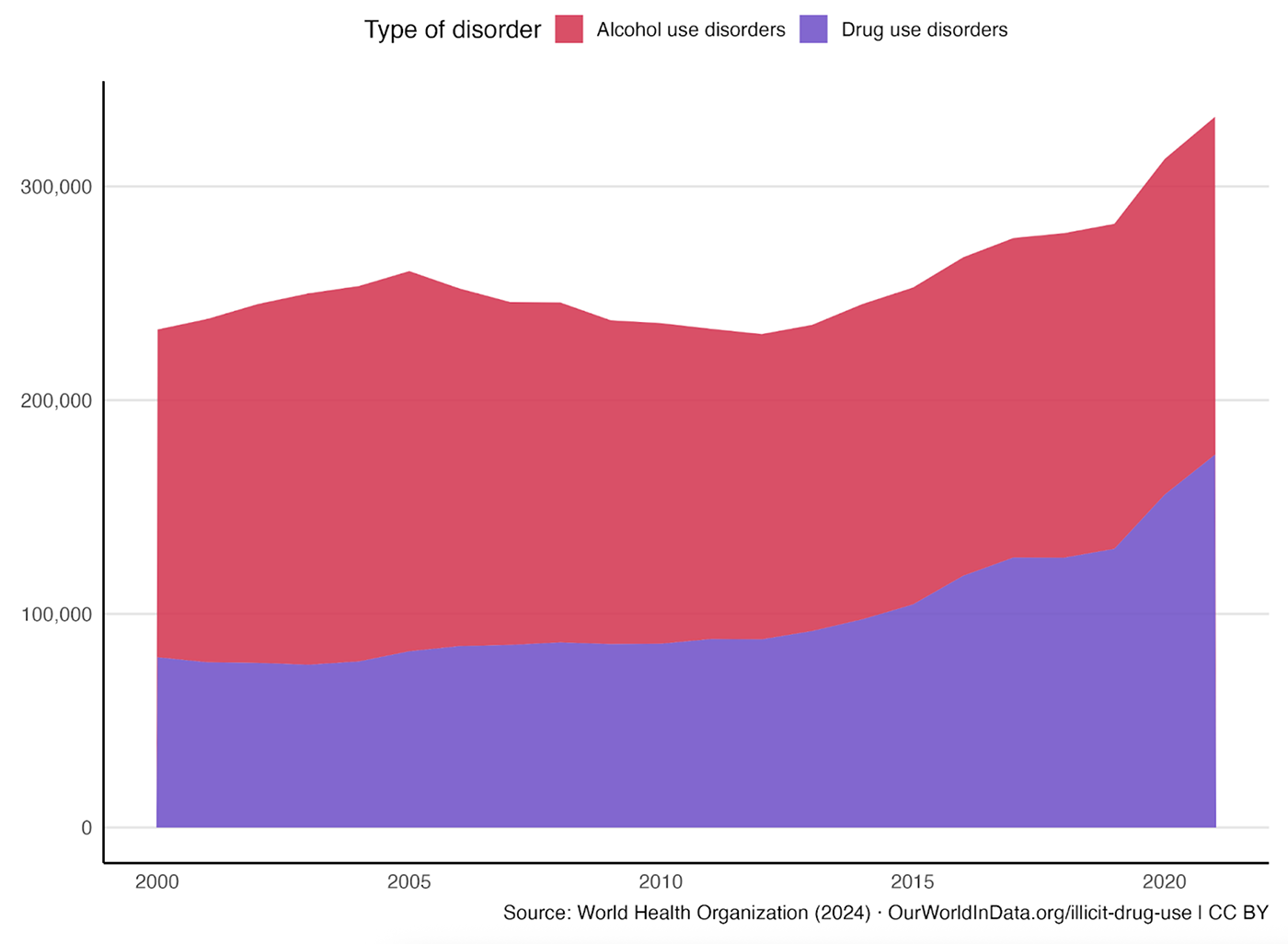

Alcohol and drug use disorders are attributable to hundreds of thousands of deaths globally. As shown in Figure 2 in Section 1, combined, this is 0.4% of all deaths, comparable to homicide (0.6%), and more than those who die from malnutrition (0.3%) or war (0.1%).

These figures are just for people dying from substance and alcohol abuse disorders; there are many more deaths once one includes all who died because of these substances (e.g., alcohol use more generally is attributable to 5% of all deaths; WHO, 2024). These numbers, unfortunately, have grown massively for substance use due to the opioid epidemic in the past decade.

Figure 10: Global substance use disorder deaths (excluding suicide), 2000 to 2021

As with most mental disorders, few cases of alcohol or substance use disorders are treated, with only 9.3% receiving treatment in LMICs, and less than 4.3% receiving adequate treatment in LMICs.

Potential solutions

There are solutions for alcohol and substance abuse problems, and even potential funding opportunities. However, formal evaluations of their wellbeing cost-effectiveness have yet to be conducted, which limits the ability to evaluate charities in these terms.

Given the limited evidence, it’s unclear which intervention is the best bet in this area. Advocacy for raising the price of alcohol appears to be the most promising macro-scale intervention. Either directly delivering or working to integrate with primary care, brief behavioural interventions like motivational interviewing for alcohol or substance use seem potentially promising on a micro-scale. But the effectiveness of brief interventions is smaller and more uncertain compared to psychotherapy for depression, anxiety, or anti-social behaviour.

Pharmacological interventions

Drugs work for reducing alcohol and substance use in high-income countries (e.g., 5 fewer days of drinking per month). But there’s limited evidence (around 4 RCTs) for their effectiveness in low and middle-income countries. And even if their efficacy generalised, there are often more implementation difficulties and cost concerns with scaling drug delivery in LMICs.

Policy-level interventions

These are well studied (one recent study reports 62 studies of policies in LMICs) and effective at reducing alcohol use. For example, doubling alcohol taxes may reduce alcohol consumption by 10%. Although some policies (such as alcohol bans) may have harmful effects on wellbeing in the short term.

Less is known about the policies to reduce substance use, but some studies indicate that policies to prevent substance abuse can backfire. This suggests that developing policy approaches to addressing substance use may be relatively tricky.

Brief interventions

Brief interventions to reduce substance use are short, structured, conversation-based interventions aimed at helping individuals recognise and reduce risky or harmful substance use. A common type of intervention is motivational interviewing, where the aim is to elicit motivation to change from the individual in a non-directive manner. These are often deployed in primary care settings.

Evidence from 34 trials, mostly from high-income countries, finds that brief interventions can reduce alcohol consumption by 8% after one year. Brief interventions have also been found to reduce alcohol and substance use in LMICs, but this is based on fewer studies, and the effects tend not to persist after a year.

The promise of brief or single-session interventions is that they can be delivered cheaply and widely. Estimates suggest that these can be delivered at costs ranging from $15 to $33.

There are no wellbeing cost-effectiveness analyses of brief interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use. Still, previous health-based cost-effectiveness analyses have placed them amongst the most cost-effective interventions to improve mental health.

Organisations to evaluate and potentially fund

There are some noteworthy organisations advocating for policies to reduce alcohol consumption and researching or delivering brief interventions to reduce substance abuse. Most of these are focused on alcohol use. But they have not yet been evaluated for cost-effectiveness.

- Sangath, a mental health and research organisation in India, is testing scalable interventions to integrate brief psychological interventions into standard healthcare for alcohol use disorder. Other research programmes are working on similar issues, but Sangath has the most robust track record of scaling successful interventions among them.

- Reset Alcohol is an initiative by Vital Strategies. They reportedly contributed to the passage of a recent alcohol tax in Sri Lanka.

- Concentric Policies is an AIM-incubated charity that works to expand the adoption of evidence-based health policies in LMICs. One of their areas of focus is alcohol, but they primarily work on tobacco.

While there is some evidence for effective interventions to treat or prevent alcohol and substance use disorders, more work is needed to understand the most cost-effective funding opportunities for research or implementation.

2.5 Thought disorders such as schizophrenia

“That’s a common myth that schizophrenia means split personality. The schizophrenic mind is not so much split as shattered. I like to say schizophrenia is like a waking nightmare. [When you’re having a nightmare] you’ve got all the bizarre images and impossible things happening, and you’re terrified, but then you just sit bolt upright in bed and the experience dissipates. No such luck with a schizophrenic episode — you can’t just open your eyes and make it go away.”

Elyn Saks, law professor at USC and author of The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness

The problem

Thought disorders are “understood as disturbance in the organisation and expression of thought”. Thought disorders like schizophrenia involve both ‘positive’ (in addition to normal functioning) symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions) and ‘negative’ (in subtraction from normal functioning) symptoms (e.g., lack of motivation, emotional flatness).

These mental illnesses are sometimes considered the most extreme and challenging to treat, and commonly face an isolating and distressing stigma. As shown in Section 1, thought disorders like schizophrenia, while they affect 0.3% of the population, are one of the worst conditions for life satisfaction.

Like most mental health conditions, few receive adequate treatment, especially in LMICs. Indeed, one study found that the most common initial point of contact for people experiencing psychosis in LMICs was traditional faith healers.

Potential solutions

We do not know of cost-effective programmes to reduce the wellbeing burden of thought disorders in LMICs. It would be valuable to conduct further research into the most effective interventions, explore ways to make them more cost-effective, and identify available funding opportunities.

Antipsychotic medications

Antipsychotic medications are generally effective at reducing positive symptoms and psychological interventions (such as cognitive behavioural therapy or social skills training) are often needed to treat negative symptoms. A combination of both is considered adequate and usually recommended (for example, by the WHO).

For example, with schizophrenia, this typically involves first-generation antipsychotics like haloperidol or affordable generics such as risperidone, paired with psychoeducation for family members to improve treatment adherence, reduce relapse, and further increase the benefits of drug treatment.

Community-based interventions

A meta-analysis of 7 studies in LMICs found that community-based interventions – involving psychoeducation, lay-assisted rehabilitation, and family involvement in care – are effective, but the existing evidence is limited.

Less is known about the policies to reduce substance use, but some studies indicate that policies to prevent substance abuse can backfire. This suggests that developing policy approaches to addressing substance use may be relatively tricky.

Unfortunately, the cost of treating thought disorders is higher than for other mental health conditions. For example, in a study comparing five low and middle-income countries, the authors concluded:

“Schizophrenia is generally more expensive to treat per person than either depression or epilepsy, especially if newer antipsychotic medications are used. In Nigeria, treating schizophrenia with older antipsychotic drugs falls between US$200 and 300, whereas newer antipsychotic drugs were estimated to cost over US$6000 per year. Similarly, in Brazil, treatment with older, first-generation antipsychotic drugs is as low as US$120 per patient per year, but second-generation drugs cost over US$4000 per person annually. In Thailand, direct medical costs for drug treatment in combination with family interventions cost US$764 per patient per year.”

The cost is high because treatment is much more intensive and often requires long-term care. One study attempting to be cost-saving found a treatment cost of $627 over six months of treatment.

There have been no wellbeing analyses of the cost-effectiveness of treating thought disorders, but existing health-based analyses suggest it’s much less cost-effective than treating other conditions. Patel et al. (2016) indicate that treating schizophrenia is much less cost-effective from a DALY perspective compared to treating epilepsy, alcohol, or mood disorders (i.e., $236 – $407 per DALY for alcohol compared to $1,427 – $8,390 for treating schizophrenia).

Potential organisations to fund

There are over thirty research projects and organisations working in LMICs that focus on treating thought disorders, as listed in the Mental Health Innovation Network. However, no analysis has been conducted to determine which are the most cost-effective in improving wellbeing.

Given that there do not currently appear to be any exceptionally cost-effective programmes to reduce the wellbeing burden of thought disorders, it would be valuable to conduct further research into the best interventions, explore ways to make them more cost-effective, and identify available funding opportunities.

3. Building a field

Funding and research

While scalable strategies are an important foundation, real progress depends on stronger collaboration and greater resource mobilisation. This section highlights the decline in mental health funding despite rising prevalence and burden, and outlines key actions that can drive meaningful change.

Introduction

The field of global mental health faces challenges and opportunities.

- Funding has declined from $250 million in 2019 to $150 million in 2022 (the most recent IHME data), even as the prevalence and burden of mental health conditions rose over that same timeframe.

- There is no equivalent to the Gates Foundation for mental health. The backbone of funding comes from small to medium-sized foundations, many of which focus on mental health among other priorities.

- Given this scarcity, it’s more important than ever to allocate resources where they’ll have the greatest impact. When funding is constrained, additional investments can have an outsized influence—shaping field priorities and steering mental health toward more effective approaches.

- We aim to grow the group of funders, researchers, and practitioners working to identify and expand the most effective solutions.

3.1 Funding

As we explained in Section 1, global mental health is clearly and critically under-resourced relative to the size and severity of its harm. This is why it is particularly important now to focus on highly impactful funding opportunities.

Global mental health receives relatively little philanthropic funding, around $100 million per year, which is declining (as shown below). Compare this philanthropic funding for cancer (Cancer UK alone raised £463 million from donations), or other neglected problems like HIV/AIDS ($55 billion) and malaria ($2.4 billion). The total amount of funding for global mental health has been declining, a trend that is likely to continue.

State of global mental health funding: small and shrinking

Financing for global mental health has declined since its 2019 peak, before accounting for 2025 budget cuts from major donors, including the USA, UK, France, and Germany, which would fall under bilateral aid.

Figure 11: International assistance for mental health

3.2 Funders

Who are the largest, most influential funders of global mental health?

We don’t have data on the exact sources of funding for global mental health. However, we believe we can confidently state that there is nothing like a Gates Foundation dedicated to mental health. Most global mental health funding appears to be a small share of the disbursements from large foundations or a substantial share of the disbursements from smaller foundations.

Below, we collected a list of the largest global mental health funders we could find. We don’t expect this to be an exhaustive list. If you think we’re missing someone, please let us know.

Table of large mental health funders (view on computer)

| Funder | Share of total | Type | MH spend $m/year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wellcome | 5.71% | Research | $120.60 |

| ICONIQ YMWB Co-Lab | 60.24% | Direct | $13.49 |

| Enlight Foundation | 25.00% | Direct | $11.88 |

| Inner Foundation | 100.00% | Direct | $11.50 |

| Ford Foundation | 2.03% | Direct | $10.80 |

| Grand Challenges Canada | 20.00% | Research and delivery | $7.60 |

| Simons Foundation | 1.27% | Direct | $7.20 |

| Open Society Foundations | 0.37% | Direct | $5.60 |

| Oak Foundation | 1.20% | Direct | $5.60 |

| The being initiative / Fondation Botnar | 100.00% | Research | $5.04 |

| Mental Health Funding Circle | 100.00% | Direct | $0.93 |

| Gates Foundation | 0.01% | Research | $0.53 |

| Agency fund | 11.16% | Research LMICs | $0.50 |

3.3 Funding direct impact through organisations

There are a variety of focused organisations directly aiming to cost-effectively improve global mental health that could receive funding. This is not an exhaustive account, but a sample of promising organisations working directly on these problems.

Organisations scaling psychotherapy for common mental health disorders in LMICs

These organisations focus on delivering evidence-based, scalable, and often low-cost interventions – primarily psychotherapy, often lay-delivered or with other processes to increase cost-effectiveness – for common mental health disorders like depression and anxiety in LMICs:

- StrongMinds (Uganda, Zambia): Provides group interpersonal therapy to women with depression, treating around 400,000 individuals per year. Evaluations by the Happier Lives Institute suggest it is a top charity at cost-effectively improving wellbeing. For every $1,000 invested, 40 WELLBYs are produced.

- Friendship Bench (Zimbabwe): Trains lay health workers (called “grandmothers”) to deliver problem-solving therapy for depression and anxiety on community benches, treating around 300,000 individuals annually. Evaluations by the Happier Lives Institute suggest it is a top charity at cost-effectively improving wellbeing. For every $1,000 invested, 49 WELLBYs are produced.

- Sangath (India): A research-to-practice organisation led by global mental health leaders (e.g., Vikram Patel), Sangath develops and trials low-cost mental health interventions, often delivered by non-specialists (task-sharing). They are involved in developing and scaling treatments to a range of mental health conditions for different demographics: from improving youth wellbeing in schools, to working on substance use and improving detection of schizophrenia in primary care.

- Shamiri Institute (Kenya): Delivers brief character strength and growth mindset interventions to adolescents in schools, serving approximately 100,000 students annually. Their programme is studied in several RCTs, though its cost-effectiveness has not yet been formally evaluated.

- FineMind (Uganda): Partners with clinics to train lay providers and deliver problem management plus, one of the best studied therapy modalities in LMICs, reaching 5,000 people annually. Their cost-effectiveness has not yet been formally evaluated.

- Vida Plena (Ecuador): Provides group interpersonal therapy to low-income women. Currently reaching ~1,000 people per year.

Organisations innovating in delivery mechanisms for treating common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety

These groups aim to create more scalable, accessible, or affordable interventions through digital tools or novel workforce models:

- Kaya Guides (India): Offers guided self-help therapy through a WhatsApp-based chatbot, integrating evidence-based behavioural techniques with optional human support.

- SameSame Collective (Africa): Builds digital mental health resources specifically for queer youth in Africa. Provides culturally competent content and safe digital spaces.

- Overcome (Global): Matches clients with trained graduate student volunteers to provide low-cost or free teletherapy. Aims to address therapist bottlenecks and build a replicable, scalable model.

- Canopie (USA): Delivers digital mental health programs for perinatal mental health, using evidence-informed content to support mothers during and after pregnancy. Focused on reducing postpartum depression and anxiety. Currently US-based, but the model could inform LMIC adaptations.

Organisations scaling psychotherapy to reduce anti-social behaviour and criminality in LMICs

- ACTRA (Colombia): Is currently developing a promising programme in coordination with the world’s leading experts on CBT and crime.

Organisations working to prevent suicides in LMICs

- Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention or CPSP (Global): is potentially the only global organisation working to reduce suicide deaths from pesticides. The CPSP played a critical role in getting highly toxic pesticides commonly used for suicide banned from Nepal, potentially saving hundreds each year.

3.4 Funding research

Despite much of the spending on global mental health going to research, research is still neglected relative to other health conditions. The percentage of research investments attributed to mental health research is disproportionately less than the percentage of the burden caused by mental health conditions.

For example, according to a report on funding for mental health, cancer research in the UK receives £611.7 million annually, compared to just £124.3 million for mental health. This is despite mental health affecting nearly five times as many people (13.4 million vs. 2.7 million). This translates to £228 spent per person affected by cancer, but only £9 for mental health, a 25-fold difference. Additionally, 68.2% of cancer research is funded by fundraising charities, whereas just 2.7% of mental health research is, highlighting a stark gap in charitable support.

The US National Institutes for Health and Mental Health are the premier funders of mental health research in the world. Their budgets are expected to fall precipitously over the next few years.

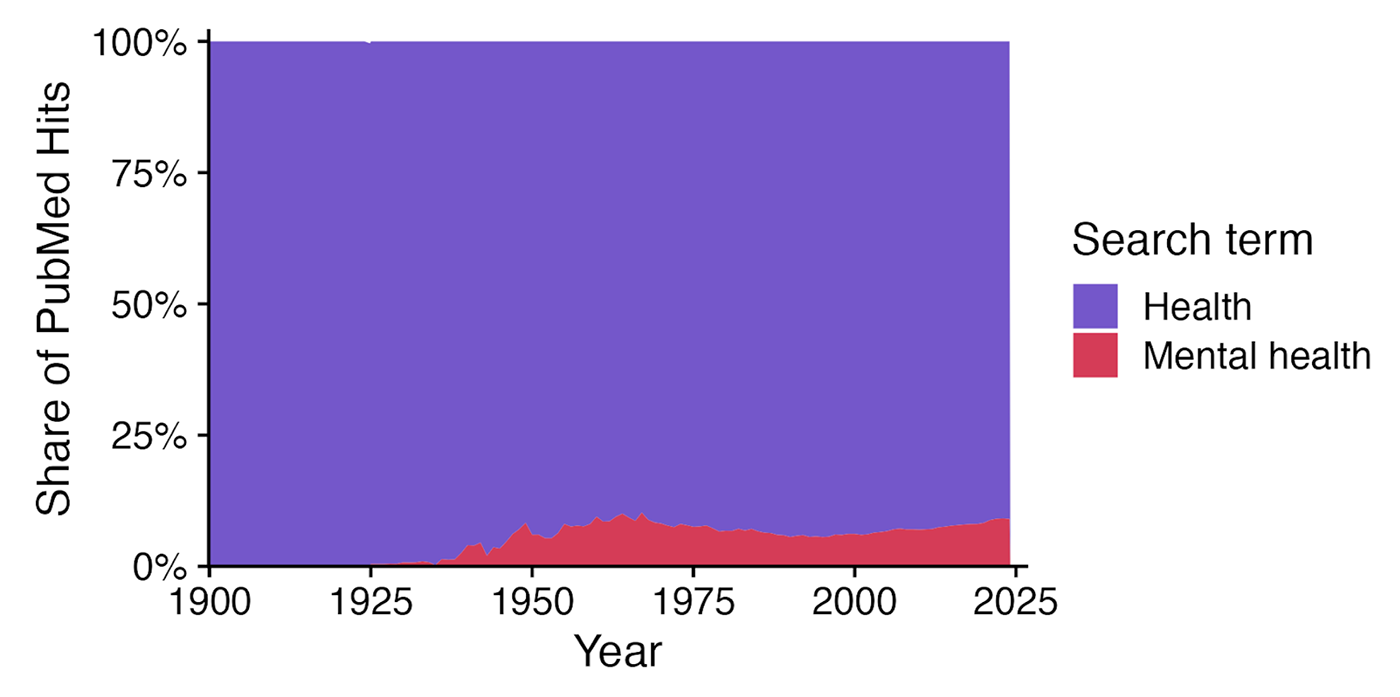

As with spending, the volume of mental health research may also be disproportionate to its health burden. For example, mental health represents 7.67% of global DALYs, yet mental health articles in the PubMed database peaked at just 10% of all health articles in 1967. While not a perfect measure, this suggests mental health receives less research attention than its burden warrants.

Figure 12: Number of PubMed records related to health and mental health

Critically, it’s not just about how much is funded, but what gets funded. While we know many interventions are effective, we lack robust comparisons of which interventions deliver the most impact per dollar spent—precisely the information that would help philanthropists and governments allocate scarce resources better.

Research priorities

Aside from investing more in research, there are specific areas which would be valuable for improving how funding in global mental health is spent:

- More (wellbeing) cost-effectiveness analysis, including for interventions that may improve wellbeing by treating broader environmental determinants of distress (e.g., extreme poverty or lead poisoning). Very little is known about the most cost-effective ways to improve global mental health.

- More innovation is needed to find, in LMICs, cost-effective treatments and delivery methods for substance and thought disorders.

- There are other conditions not discussed in this report, such as insomnia, that should be integrated into the story of global mental health. For example, insomnia isn’t listed as a mental health condition in the Global Burden of Disease (which is why it was not included in this report). Still, it is reportedly experienced by 16% of the world’s population in some form. (Benjafield et al., 2025)

- Even for the interventions where evidence is available, a large share of the wellbeing impact is uncaptured. This is because researchers rarely, if ever, track the mental wellbeing of household members of the recipient of a mental health intervention (spillovers). We discussed the importance of mental health spillovers in Section 1.1.3, but we provide a more detailed description of the research in the box below.

Why study household mental health and wellbeing spillovers?

Incorporating household spillovers is important because it can clearly change how we prioritise different interventions. The Happier Lives Institute’s comparison of cash transfers and psychotherapy changed dramatically after the inclusion of household spillovers. Where the effects of psychotherapy doubled, and the impact of cash transfers roughly quadrupled.

There is a notable absence of evidence about spillovers (e.g., Chapman et al., 2022; Lawrence et al., 2025). But absence of evidence should not be misconstrued as evidence of absence. The most thorough discussion of spillovers we know of (and specifically related to psychotherapy for depression) is in the Happier Lives Institute’s meta-analysis of psychotherapy in LMICs. The report concludes that the spillover ratio for psychotherapy is 16%, but this is primarily based on two studies.

We know close to nothing about what may be a large part, in some cases most, of the benefit of many mental health interventions. This is a gap in the evidence worth closing.

We hope the best interventions of the future will be substantially more cost-effective than those we know of today. Many emerging and experimental treatments deserve further research or evaluation and comparison to other interventions. We expect to see further innovation on how to bring costs down without a comparable drop in effectiveness so that we can lessen the burden and help people live happier lives.

Conclusion

Conditions like anxiety or depression are amongst the worst of life’s common misfortunes, reducing life satisfaction more than debt, divorce, or unemployment, and in extreme cases leading to human rights abuses like chaining. And these are common, affecting about 1 in 6 people globally.

Government and development assistance neglect mental healthcare. Despite having a comparable burden on health to HIV/AIDs, Malaria, and tuberculosis combined, it receives 0.22% of the health-directed aid (compared to 35.87% for the other three diseases combined). The consequence is that most people, even in rich countries, receive no treatment. In the world, only 6.9% receive adequate treatment. The levels are lower in LMICs, with, for example, only 3% receiving adequate treatment for depression in LMICs.

Yet this isn’t because there are no solutions. In fact, most common mental health disorders like depression and anxiety have been proven to be effectively treatable for less than $50 a person, and these treatments are cost-effective. The field of global mental health has been losing funding, and few of its backers are primarily focused on it as an issue. The Bloom Wellbeing Fund, together with a growing group of philanthropists in the Mental Health Funding Circle, is working to change this by coordinating and catalysing investment in the highest impact mental health interventions.

Here’s how you can help:

- Partner with Bloom or the Mental Health Funding Circle to build a field of effective giving dedicated to supporting mental wellbeing.

- Fund highly impactful charities solving these problems, or the research needed to find the next wave of even more effective solutions.

- Research: We need more evaluations of charities and better evidence on their effectiveness.

- Join the conversation: we’d love to hear your ideas, feedback, or questions.

Thank you!

We would like to thank the following reviewers for their helpful feedback: Sam Bernecker, Ulf Graf and Maggie Moss.